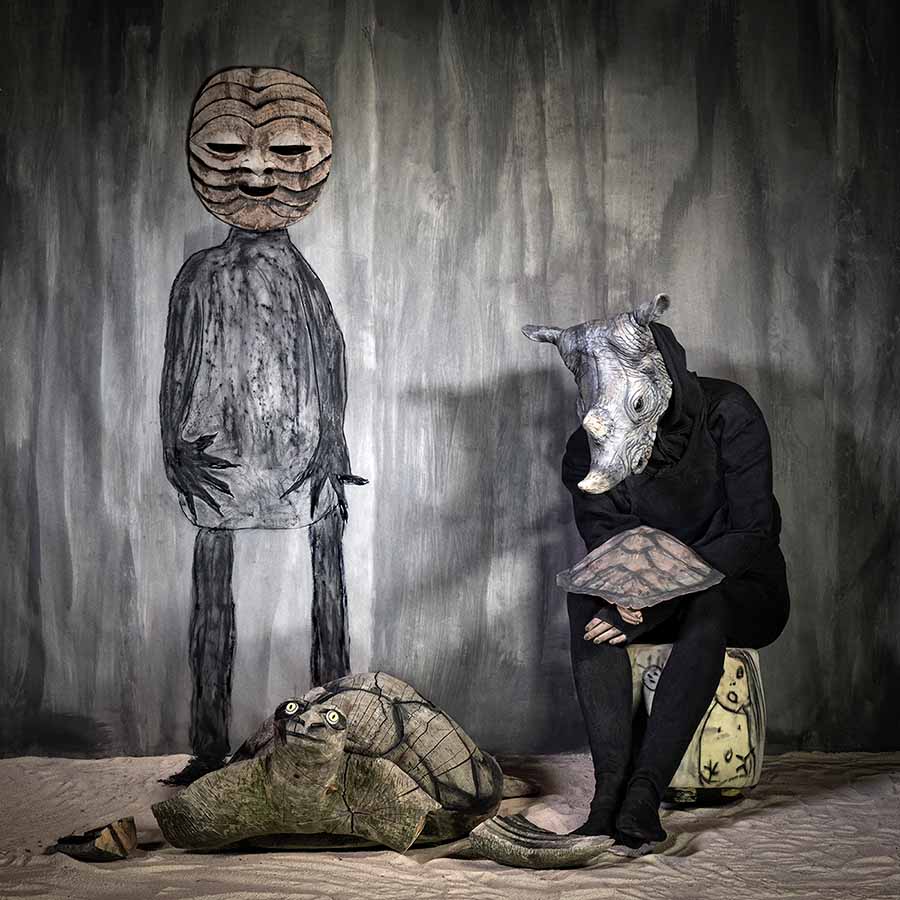

“This year I am representing South Africa at the Venice Biennale with a project called

Theatre of Apparitions”, says Roger Ballen. “I used lightboxes to illuminate the photographs, so they look like pictures of a world of ghosts.”

Despondent, 2020. All photographs are reproduced with the kind permission of Roger Ballen, unless otherwise indicated

References to the theatre and phantasmagorical characters have played a recurring role in Ballen’s long career. They are an essential part of his aesthetic that has been defined as “

Ballenesque”, by the postcolonial historian and critic, Robert J.C. Young. Windowless walls, masked human figures, animals and objects juxtaposed in an apparently incongruous way: all this and more has helped create a distinctive oeuvre of artworks that has influenced and inspired many other artists.

In our interview with Roger Ballen, we began by asking him to reconstruct his career in three steps with regard to his use of light and colour and then we moved on to talk about his Inside Out Centre for the Arts, the institution for the promotion of African art that he has founded and helped create in Johannesburg and which will officially open in Autumn 2022.

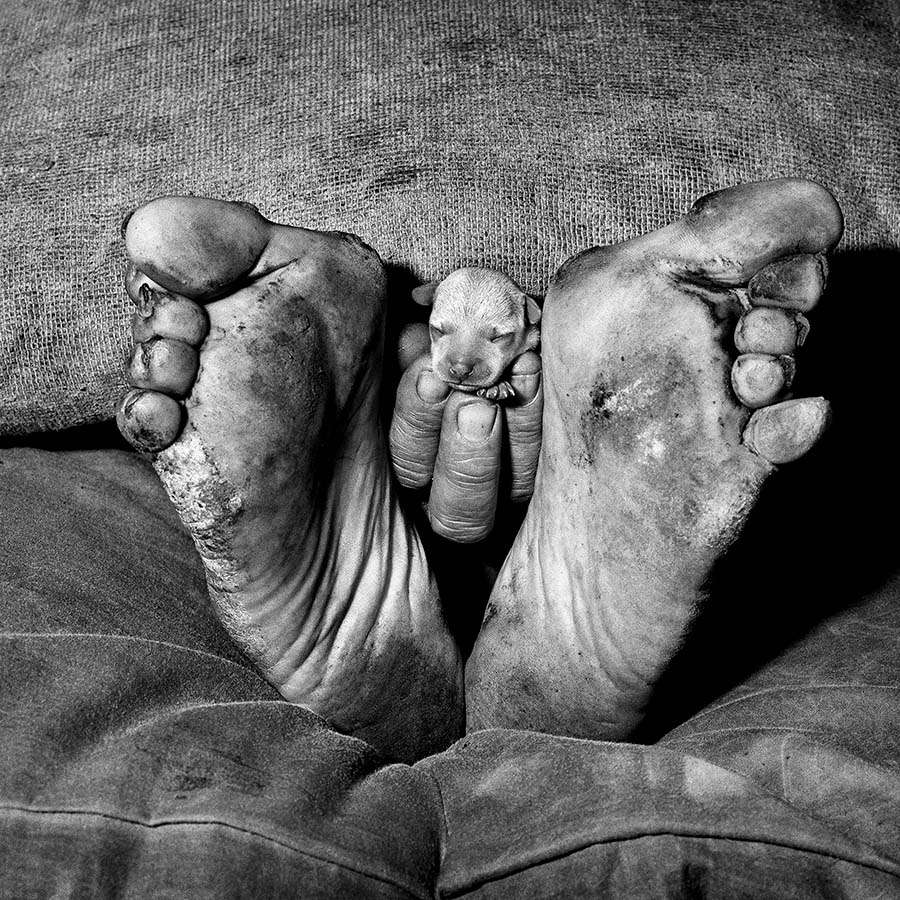

Five hands, 2006

STREET PHOTOGRAPHY

“The first part of my experience was from about 1967 to 1982. During this time, I would call myself a street photographer, and so for example between 1973 and 1978 I hitchhiked from Cairo to Cape town and from Istanbul to New Guinea. I did a lot of travelling. I would go outside and walk around where I was and try and find the pictures I was looking for. The lighting conditions I sought after were in the early morning or later in the day, when the light was subdued, because I was working in black and white and when there was a lot of sunlight, during the later morning or the afternoon, it was very difficult to take pictures. It was easier to work where it was very cloudy. I used to say that if I had been up in England or Ireland or the Netherlands, my job would have been much easier. By the way, Damiani publisher from Bologna is republishing my

Boyhood book from that time in the fall of this year.”

Froggy Boy, USA 1977

MOVE TO SOUTH AFRICA

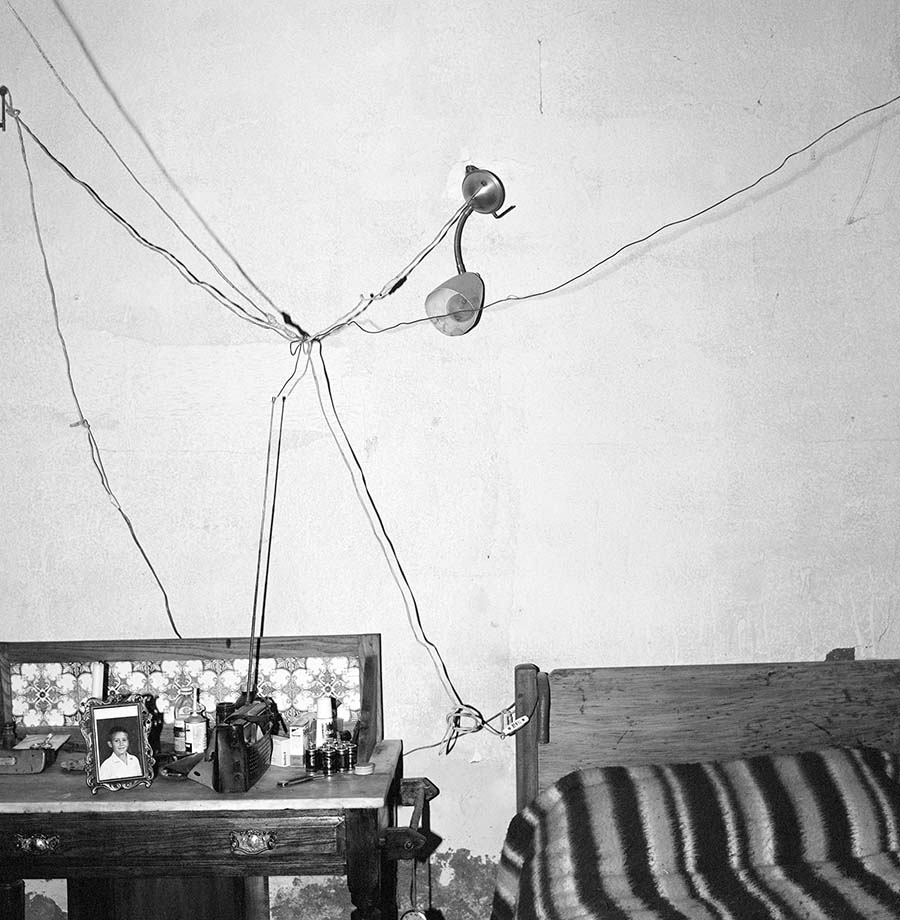

“I kept using natural lighting until I permanently moved to Johannesburg, South Africa, in 1982. The light here is extremely bright most of the year, there’s not many clouds, from April to October it doesn’t rain, so it was very difficult to do black and white street photography, especially to get up early and walk around and in a lot of places nobody was around, so it became a little frustrating. Just by chance, I started to meet people and go inside their houses. Since the lighting was very poor in these houses, some people didn’t even have electricity, I had a small flash and I started using it. I’d never really taken photos inside.”

Bedroom of railway worker, De Aar 1984

LIGHT, TECHNOLOGY, COLOUR

“Until 2016 all my pictures were flash. In the earlier works the flash was attached to the camera, and beginning about 2008-2009 I used a bigger flash, no longer attached to the camera and I used two strobes at a 45° angle. Beginning in 2016, I started using LEDs, and this was made possible – this is a very important point – because I moved away from film to digital. When I was using film, the ISO was about 400 so the shutter speed was very low. As you can see, my photos have a lot of animals in them: birds, rats, dogs, cats, and when they moved they would be blurred. While I was making the video for my book called

Ballenesque, Roger Ballen: A Retrospective. In 2016, Leica gave me a camera. Just by chance I started taking colour pictures with this camera and I was really amazed at how the colour turned out, so I kept working in colour and because I had this digital camera, I could push the ISO up to 1600 or 3200 and I was able to use led lights in my work. I still use LEDS, I haven’t used a flash for some time.”

Puppy between feet, 1999

Before that did you not believe in colour photography?

When I started taking pictures in the 60s, serious photographers only used black and white. Documentary photographers didn't think of themselves as artists. I grew up in a culture that believed black and white was the only way to document the world around you with a camera. My pictures were very well received so I never felt uncomfortable with black and white, while colour felt plastic, inauthentic. It was only when I got a Leica camera in 2016 that I started taking pictures with it, that I realised that my aesthetic could be equally represented in colour as it did in black and white. The colours didn't have to be bright and glorious bursting with tone, they could be very subdued. When you look at them you immediately know that I took them. My aesthetic keeps expanding in all sorts of directions. Colour is an interesting challenge, I really enjoyed it. After 50 years it was a big change.

Leopard Lady, 2019

You often focus on the interior rather than the exterior world. Is that what the name of the Inside Out Centre for the Arts you are about to open in Johannesburg refers to?

It took me a long time to come up with the name. First, it was the Roger Ballen Centre for Photography, but then, I do more than photography, and I wanted to show more than photography in the space. Then it became “Roger Ballen Centre for the Arts” but there are a million other places in the world like that. What is so great about that? What is the place about? I just couldn't get to the right name. Eventually it came to me, “Inside Out”. That's what my work is about: it's a psychological viewpoint. It's taking something that's in the back of the head, in the back of the mind and manifesting it in a photograph. So, when you look at one of my photos or visit the centre, I'm hoping that what you see connects with your inner mind and then ultimately reveals something to you, to your consciousness, one way or another, consciously or unconsciously. The exhibitions that we will be showing here soon will be 1. psychologically orientated; 2. Have something to do with Africa; 3. Have something to do with the so called Ballenesque; 4. Should be relevant to the community in South Africa. In addition, the exhibition should be an aesthetic and an educational experience. The upcoming show will be focused on the destruction of wildlife during the colonial period in Africa during the period 1860 to 1940, as well as my Ballenesque interpretation of this concept, this is a more aesthetic and psychological approach that contrasts with the more documentary exhibition, which contains photographs, postcards, guns, relics from over a hundred years ago.

The Inside Out Centre of the Arts (photo: Marguerite Rossouw)

Do you work with curators or lighting designers for your exhibitions?

I’ve had hundreds of exhibitions over the years. I have very experienced people coming in with suggestions, but I feel confident of my abilities, and from iGuzzini I got superb lighting. Because there's a computerised aspect to the lighting, over time we can take one light and bring it down, bring the other one up. The lighting in the two parts of the exhibition is slightly different. In the documentary part, the lighting will be on particular objects in the exhibition – whether it might be posters or stuffed animals or old photos or display canvas – the purpose is really to show things in a very specific, objective way so people understand what they are looking at and can say "this is interesting for me, I’m learning something about this historical period". Downstairs, where my exhibition is, we’re trying to use light in a more aesthetic way, so it has more atmosphere and it can go from light to dark, from highly focused to one that is broadly focused. So, the exhibition is not monotonous lighting wise. A lot of people in South Africa probably have never been to a museum or an art show and I think that they can fully appreciate the topic here. I’ve met several people who'd never been in a museum before and seem enthusiastic, and it's a great feeling when that happens because then you know that what you are doing is communicating to people who've never had that experience before.

An interior view of the Inside Out Centre for the Arts (photo: Marguerite Rossouw)